„Plans are nothing

planning is everything“

Dwight D. Eisenhower

The current economic situation (here), as well as the sharp rise in the number of corporate insolvencies in recent months (here, in German) prove that the German economy is in crisis mode. Of course, this crisis is not without consequences for individual companies. The following article explains what to do if the managing director recognises crisis signals in “his” company or receives a specific “crisis warning” from one of his advisors (see here for background information).

What is a “corporate crisis”?

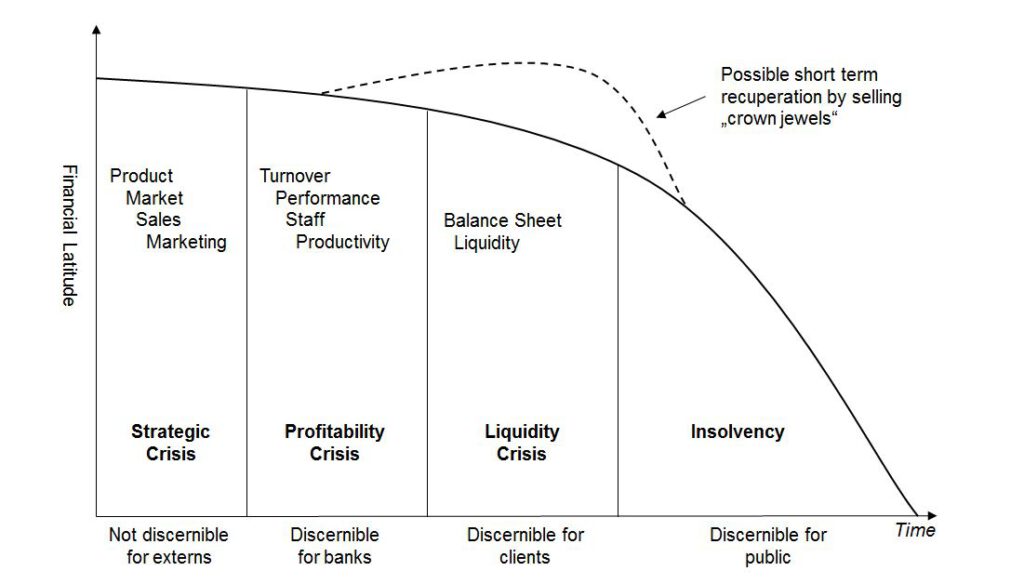

Not every crisis in a company is an immediate threat to its existence; rather, a corporate crisis escalates over several (business) stages, as the following diagram (the so-called “crisis progression curve“) illustrates:

In its groundbreaking judgement from January 2017 (more details here, judgement here, para. 28), the BGH describes specific events that, from a legal perspective, should lead to a “review of the company’s going concern prospects” at the latest “if the company has not generated any profits in the past, cannot easily access financial resources and is at risk of over-indebtedness in its balance sheet or has even already done so.” In other words, at the latest when losses have eroded equity and the payment of invoices due is not guaranteed in the future, the company is in a “crisis” from a legal perspective.

What does the management have to consider?

It is not only since the entry into force of Section 1 StaRUG (for details regarding this German Act on the “preventive restructuring mechanism”, cf. here) that the management has had to establish a functioning “early risk warning system” in the company that enables it to recognise (internal and external!) crisis symptoms at an early stage (see primarily on external risk detection in more detail here and here).

If the management recognises on the basis of an (internal) early risk warningsystem set up in accordance with these requirements, for example, that the loss of half of the share capital is imminent (cf. e.g. § 49 GmbHG), it should not only inform the shareholders accordingly to avoid liability (otherwise there is also a risk of criminal liability, cf. § 84 GmbHG), but also start directly with a (turnaround) planning appropriate to the situation. Otherwise, there is a risk that the steps necessary for the company’s recovery can no longer be implemented before the obligation to file for insolvency arises.

What needs to be considered when drawing up a “reorganisation concept”?

Over the years, several standards have been established in Germany on how to proceed in the event of a corporate crisis.

a) First of all, several phases of the reorganisation are decided: Consultants who are confronted with the corresponding question in the company often resort to an initial – still superficial – test (so-called “quick check”), in which the status of the company is first roughly determined in order to provide an overview. Such a quick check can, for example, address the following four questions:

- Where is the company on the crisis progression curve (crisis stage)?

- Does the current business model work? (Is the company “worth restructuring”? See e.g. under ESG aspects here)

- Is the liquidity sufficient for the reorganisation? (If not, in case of doubt there is insolvency according to § 17 InsO)

- Where is “leadership”? (Asks the question of whether the company management is in a position to ensure a sustainable reorganisation).

b) Based on the findings of the quick check, initial measures may need to be implemented that at least prevent the grounds for insolvency from materialising in the short term (safeguarding the company’s ability to continue as a going concern). If the grounds for insolvency have already occurred and a (sustainable) turnaround within the deadlines set by § 15a InsO does not appear realistic, the management may have to file for insolvency.

If stabilisation measures are not (yet) necessary or if the ability to continue as a going concern is secured, the necessary steps to turn around the company must be planned. Two standards have become established in practice for this purpose, namely the so-called “IDW Standard S6” for reorganisation concepts (see here for the current status (in German); the IDW already published a supplementary version of the standard last year (“IDW ES 6“, here, in German), which is taken into account in planning). On the other hand, case law itself has set out framework conditions in numerous judgements, on the basis of which it examines whether a company restructuring, even if it has failed, does not nevertheless lead to management liability (these so-called “case law rules” have mostly been summarised by banks, see a good overview here, in German). Both the IDW S6 and the case law rules present problems of their own – especially for managers who are not regularly involved in turnarounds: The IDW S6 is primarily aimed at larger companies due to the level of detail required – even if the current version incorporates the case law rules as far as possible. The case law rules, on the other hand, are too abstract and not systematised in themselves.

In practice, the following rough structure (based on the illustrative section in IDW S2 on insolvency plans (here, in German) has therefore become established for reorganisation planning:

(1) Presentation of the company (data / history)

- Historical development

Legal circumstances

- Economic circumstances

- Net assets, financial position and results of operations

(2) Analysis of the company (causes of the crisis)

- Where does the company stand on the crisis trajectory?

- Reasons for the company crisis

(3) Mission statement of the reorganised company

- Worthiness of reorganisation?

- Sustainable competitiveness and profitability

(4) Measures to reorganise the company

- e.g. subordination

- Capital measures

(5) Integrated financial planning (plan validation calculation)

- Based on the actual situation described under 1, the effects of the measures must be quantified and summarised in an integrated corporate plan

- The prerequisite for restructuring controlling must be created by defining suitable key figures and making the restructuring plausible

As in any “normal” business planning, the standard of scenario planning has also developed in the area of turnaround planning, usually with three scenarios – “best”, “middle” and “worst” case.

Turnaround plan in place – now what?

The plan alone does not lead to restructuring – this is only possible if the restructuring measures envisaged in the plan are implemented. In case of doubt, however, the plan initially serves to negotiate with the parties involved about their respective contributions to the reorganisation – often “fresh money”.

If it is possible to “collect” these restructuring contributions, then the level of effort begins – the plan must be implemented and any restructuring measures in the company, such as the dismissal of employees, must be enforced. Often – if not already involved in the planning – a so-called “Chief Restructuring Officer” (CRO) is appointed and the previous planning team is “transformed” into a project management office (PMO), which implements or supports the restructuring steps and carries out the restructuring controlling.

Achieving the objective of the reorganisation – restoring the company’s competitiveness and profitability – often takes several years. Experience shows that the original reorganisation plan cannot be implemented unchanged during this long period. In most cases, it is necessary to adjust the plan to the changing market situation after one to two years at the latest, and often even earlier because the reorganisation plan was too optimistic. In principle, the same rules apply to this recalibration as to the original planning. A cycle is created. And there is nothing wrong with that. After all, “normal” business planning also needs to be adjusted regularly. In other words, the establishment of a continuous planning process is more important than the original plan.